Peter Sheng first applied in 2015 for funding to develop a tool designed to help managers better understand and predict the effects of sea level rise in Collier County. Though his application received a good review, the proposal was not funded that first round.

“The science review was excellent and community engagement was considered weak because I couldn’t find a proactive person in Collier County to work with me,” said Sheng, a professor emeritus in the Department of Civil & Coastal Engineering at the University of Florida.

Then Sheng met Mike Savarese. Savarese is a professor at Florida Gulf Coast University’s Department of Marine & Earth Sciences and a long-time advocate for transferring science to management.

“I showed him the proposal we sent a year before and he showed me what kind of support he was able to get from within Collier County, and we were both impressed by what the other guy was able to do,” Sheng said. “We put our science and stakeholder relationship together.”

In 2016, the two professors submitted a revised proposal. The project was funded the next year with an award of nearly $1 million from the NOAA RESTORE Science Program to build a decision-support tool designed to help resource managers in Collier County better engage in coastal planning around the effects of sea level rise.

Since that first award, the project has received additional funding from the NOAA Effects of Sea Level Rise Program through the National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science’s Competitive Research Program, the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, and directly from Collier County. It is now being expanded to include neighboring counties and to map the effects of freshwater inundation.

But a more impactful indicator of the tool’s success is that it is actively used by managers from a range of sectors, including natural resources, urban infrastructure, and cultural and archeological resources. Savarese said the tool’s broad application is a direct result of bringing in a variety of potential users from the beginning stages of planning the project.

“What I believe is one of the most unique aspects is the tool was developed in consultation with the users, and our definition of a user was very broad,” Savarese said. “When you talk to historians and archaeologists, they are usually pushed to the curb for these types of things and are not engaged. We have engaged cultural resource people from the very beginning.”

Archaeological Sites to Cultural Case Studies

Sara Ayers-Rigsby, director of Florida Public Archaeology Network’s (FPAN) southeast region, remembers attending early meetings for the tool’s development. FPAN is a statewide organization run through the University of West Florida, and the program’s southeast region is hosted at Florida Atlantic University. By engaging in those discussions, Ayers-Rigsby was able to gain a deeper understanding of how the tool would be built, and her presence in the room was a reminder to other managers to consider the impacts of archeological and cultural sites in the region.

After it was developed, Ayers-Rigsby and her FPAN colleagues used the tool to identify which sites will be threatened by saltwater inundation first. With hundreds of sites to consider, Ayers-Rigsby recruited a team of archeologists in South Florida to help sort through the data and develop a list of sites to consider.

“It was really nice with ACUNE to be able to go in and do the work ourselves and to be able to collaborate with so many other professional archeologists,” said Ayers-Rigsby, who added that accessing and using the tool was much easier than others that she has experienced.

Sheng and other tool developers worked to make the layer showing archeological sites private to other viewers because the specific locations of those sites are kept as privileged information to protect them from looting and other disruptions. The same restrictions do not apply to cultural sites, such as churches, schools, and historical locations, which can be viewed with less restrictions.

Ayers-Rigsby and her colleague Rachael Kangas, public archeology coordinator for Florida’s west central region at FPAN, used the ACUNE tool, which stands for Adaptation of Coastal Urban and Natural Ecosystems, to engage community members in the protection of those cultural sites. The two partnered with Savarese to host a meeting with representatives from stakeholder groups in Collier County, guided by the goal of finding a set of case studies to illustrate how sea level rise is threatening important cultural sites in the region.

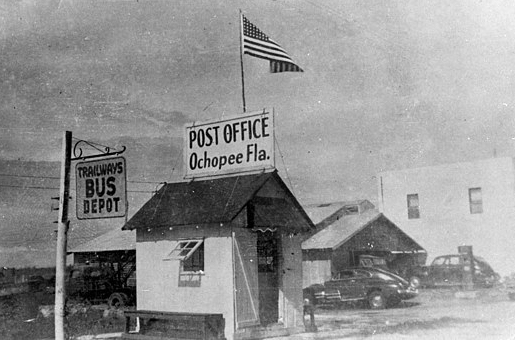

The working group identified 10 sites – many of which Ayers-Rigsby said she and Kangas would not have considered otherwise – and built a story for how each would be impacted under a range of future scenarios. The smallest post office in the country, located in the town of Ochopee, was one of the 10 sites identified.

“Even though there are a lot of really impressive archeological sites in the county, if someone has never been to them, it can sometimes be hard to convey a sense of loss when you are looking at that kind of climate modeling,” Ayers-Rigsby said. “Whereas if it’s a historical cemetery or something like that, and we show what it’s going to look like in these different scenarios – that can be more impactful.”

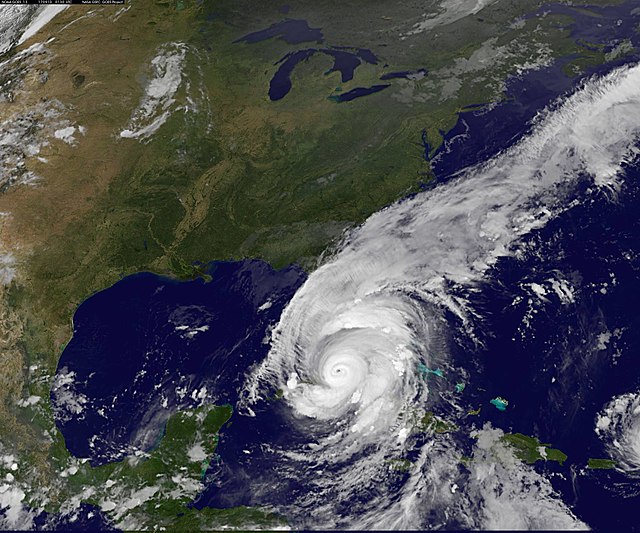

One of the unique features of the ACUNE tool is that its models consider the changes in coastal wetlands that occur alongside shifts in wind, water level, and salinity over time. Southwest Florida boasts the largest mangrove forest in the Gulf of Mexico region, which protects coastal communities against flooding by acting as a buffer to storm surges and waves during tropical storms and hurricanes.

“That might be something where it wasn’t necessarily part of the vulnerability assessment we prepared for cultural resources but let’s say after a major hurricane, that’s something I would look at because mangroves will tend to protect the sites,” Ayers-Rigsby said.

By considering mangroves and other coastal wetlands, managers can evaluate the potential for these areas to mitigate against coastal flooding. In one study led by Sheng and his colleagues, the team found that coastal wetlands prevented $13 million in structure losses in Collier County during Hurricane Irma. When they considered impacts to the area based on the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) 1% flood zone map, which considers multiple storms, they found that mangroves would have prevented $40 million from a potential $100 million in structure losses in Collier County.

“Those numbers indicate mangroves in this county are very valuable for protecting people from residential structure damage,” Sheng said.

A New Way to Model Coastal Flooding

Chad Washburn, the vice president of conservation for the Naples Botanical Garden, was also in attendance at those early planning meetings for the ACUNE tool. Washburn and his team have used the tool to help prioritize their seed collecting initiatives, and the garden’s opportunities for seed collection are tremendous.

On one nine-acre scrub habitat that the garden owns, Washburn and his team have identified 30 species of plants that are not logged in any other botanical garden collections in the world.

“That’s low hanging fruit,” Washburn said. “We should get out there and collect those.”

By including ACUNE in their analysis, the garden can better strategize which seeds to collect first – plants located in the sites that are predicted to become inundated first rise to the top of their list.

Washburn admits that he is just beginning to understand how the tool can be used to help inform the garden’s conservation efforts, and as a coastal garden, he sees potential for it to inform the master plan for the garden itself.

“I think every time I use it I come up with a new idea,” Washburn said.

The tool has also been used by multiple municipality services in Collier County and the City of Naples, such as the county’s emergency management department to help plan for encroaching storm systems.

ACUNE relies on a unique approach for predicting the impacts of future coastal flooding by using projections from climate, coastal, ecological, and economical sciences, models, and data. Considering all of these factors is crucial because future coastal flooding will be much greater than what is displayed in the FEMA flood map, which does not include the impacts of sea level rise and more intense tropical storms and hurricanes, Sheng said.

To help plan for future storms, emergency managers from Collier County can access ACUNE’s Rapid Forecasting and Mapping System, which is based on the simulated coastal flooding of more than 200 hurricanes that have previously impacted the region.

“They can invent any storm they want, or they can artificially change the characteristics of a pending storm, and see what the outcomes are likely to be and use that to inform whatever management decisions they make,” Savarese said.

A Microcosm of the Nation

Through their partnership, Savarese and Sheng have created and promoted a tool with a broad range of applications that seems to be ever-growing.

“He’s the person that understands what happens in the black box, and I seem to be the person who can communicate its value to the people here,” Savarese said.

The team is currently developing ACUNE Plus, which couples models of coastal, freshwater, and stormwater impacts to better inform decisions about urban stormwater flooding.

This year, Sheng received additional funding through a contract with Collier County to update how the data are presented in ACUNE. Savarese has also been working with neighboring Lee and Charlotte Counties to create the Southwest Florida Regional Resiliency Compact, which he calls “an alliance of local jurisdictions to deal with climate preparedness.”

By developing the tool alongside community members, Sheng, Savarese, and their team have watched cultural and knowledge shifts in the region as community members continue to learn the science behind climate, sea level rise, and storm impacts.

“It’s a case study but really a microcosm of the entire nation,” Sheng said. “We are dealing with compound flooding. We are dealing with coastal populations. People won’t move away from coastal regions. They want to continue to develop, to grow, and it is not possible. Now having this tool, they realize the future vulnerability.”

Official websites use.gov

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Official websites use.gov

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.