By Sarah McDonald

Seagrass beds are an integral part of the Gulf of Mexico ecosystem—they stabilize the sediment and remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Seagrass meadows are also a source of food and habitat for many species in the Gulf throughout their life cycles, such as shrimp, fish, and crab. But what happens to seagrass and the marine life that rely on it when the environment changes? And how do those relationships differ across the Gulf of Mexico?

Dr. Kelly Darnell, a long-time seagrass researcher and principal investigator of the project, and her team tackled these questions in a study funded by the NOAA RESTORE Science Program in 2017 that focused on one type of seagrass in particular. Turtlegrass, Thalassia testudinum, makes up a major portion of the Gulf’s seagrass meadows and is a climax species, meaning its composition will remain relatively stable as long as the surrounding environment remains unchanged.

When developing this project, she and her team had a long-standing interest in working with managers to develop actionable research that could be used in decision making. Their goal was to conduct a management-driven, Gulf-wide assessment of the use of turtlegrass as habitat by nekton, or organisms that are able to swim independently of currents, and to evaluate the support provided specifically to the economically valuable blue crab (Callinectes sapidus). They linked with managers from Texas, Louisiana, and Florida to better understand how seagrass is used as both a habitat and resource and how changes within it might impact fisheries, specifically the blue crab.

“It really provided a unique opportunity for seagrass managers, habitat managers, and fisheries managers to get together in one room and have these broad Gulf-wide discussions,” Darnell said. “Their advice, recommendations, and suggestions were incorporated into the designing and execution of the research itself.”

“This project really shaped me as a scientist,” said Dr. Christian Hayes, a faculty member at Waynesburg University, whose dissertation focused on the patterns of habitat use and trophic structure within the grass. “No one had tried this before, which is why it was exciting.”

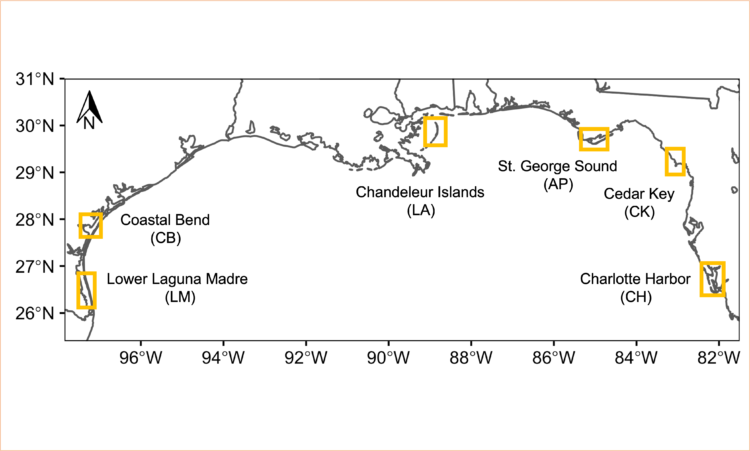

Due to the large spatial scale of the project, the team had to be strategic in how they coordinated their research plan. All the sampling and field experiments across the six sites were done simultaneously, using the same gear and the same standardized protocols to avoid data discrepancies and ensure that the results would be comparable.

We are developing our own method. That’s one of the things that we were excited about with this project, being able to address those questions directly.

Brad Furman, Research Scientist with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

The data were collected during the summer of 2018 by pulling net trawls through the water, epibenthic (or sediment surface) sleds along the seafloor, placing quadrats or square meter frames to calculate percent coverage of seagrass on the seafloor, as well as counting the number of leaves per seagrass shoot and canopy height, and other metrics. All of these procedures examined different aspects of the habitat to quantify how nekton use turtlegrass, as well as the relationships between blue crab growth and mortality and turtlegrass complexity.

Hayes remembers waking up at 5:30 a.m. most mornings to venture out on two-hour boat rides to the Chandeleur Islands in Louisiana to do his portion of the sampling.

“That summer was probably the most exhausted I’ve ever been,” Hayes recalled.

The analysis following the data collection took place over three years and, like the collection, involved a variety of methods. Hayes’ analyses relied on multivariate statistics to better understand the correlation of the conditions of the seagrass environment to the animals within it, and he found the relationship to be dependent on multiple variables. The specific animals, seagrass density, and site being studied all played a role in these relationships.

The researchers measured stable isotopes in the plants and nekton found in the seagrass meadows to find out who was eating what so they could construct food webs for each of the different seagrass systems. According to Hayes, these analyses were applied to the major species present, the overlapping species from different sites with a range of sizes, and as many primary producers–such as marsh plants, algae, and seagrass–as they could find, so the systems could be directly compared across the six sites.

Dr. Brad Furman, a research scientist with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, said the project was especially unique in its focus on examining multiple places around the Gulf of Mexico simultaneously.

“I think we have a pretty good understanding of what lives in seagrass beds and what species spend what portions of their life history there, but how different those relationships are around the Gulf of Mexico is still kind of an open question and a difficult one to get at,” Furman said. “One of the ways to approach that systematically is to do things with consistent methods at the same time in a variety of places around the Gulf of Mexico. That’s something that you can’t really get from the literature. We are developing our own method. That’s one of the things that we were excited about with this project, being able to address those questions directly.”

The project produced data across multiple levels of analysis for seagrass leaves, epiphyte samples (non-parasitic plants that grow on other plants), fish, and other ecological and biological studies—all of which were reported to fishery managers in order to maintain habitat health and production of economically valued species, such as blue crab.

Darnell saw this project through the landfall of Hurricane Michael, which passed directly over one of the research sites. But what could have been an obstacle, presented an opportunity.

“As devastating as Hurricane Michael was, it afforded us the opportunity to do an in-depth study on impacts to the seagrass ecosystems, and what we found was that the seagrass ecosystem is largely resilient, if given time to bounce back,” Darnell explained.

These findings added another layer of uniqueness to this project, as this study allowed the team to examine not only the impacts of a hurricane on the seagrasses themselves but also the animal community associated with it. Hayes said it’s rare to have a hurricane hit a study site that was examined immediately prior to impact, so the prior data was used as a control that could then be compared to the condition following the hurricane.

Following the project’s completion in May 2022, the team is optimistic about the potential to further build on the collaborations that were established during this research, applying their statistical models to economically valuable species production, and branching their initial results into further, more specialized studies.

“We’ve had really great success in terms of the reach that we’ve had from this project,” Darnell said. “We’ve been fortunate enough to work collaboratively with our expert advisory panel members, and we really hope to foster those collaborations moving forward.”

Official websites use.gov

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Official websites use.gov

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.