By Miranda Madrid

Gathered together in Dauphin Island, Alabama in late 2022, a team of researchers from graduate students and early career postdoctoral scientists to senior scientists ready presentations on their most up-to-date findings. Their expertise include climate science, watershed hydrology, water quality, economics, fisheries, physical oceanography, and ecology.

Amongst them, in almost equal numbers, are those they hope will be able to use their research, namely, representatives from state agencies and non-governmental organizations. The project lead, Dr. John Lehrter, characterizes them as “folks that are real boots on the ground, people that are implementing projects around here.”

This gathering takes a different approach. To increase the likelihood that the research will be used, the perspectives of these boots on the ground individuals, or intended users, are prioritized. The intended users are the first to present on their own organization’s priorities and projects before the research team shares their findings. The users are also asked questions by the researchers and an understanding of how they can work together grows.

John Mareska, assistant chief of fisheries in the Marine Resources Division for the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (ADCNR), recalled Lehrter’s team asking what additional data he and his staff want access to and the types of future challenges they will need information for. Mareska’s and other’s responses are then the guide for these researchers as they return to the field and lab.

These researchers and resource managers are being supported by a $2.8 million award made by the NOAA RESTORE Science Program in 2019 that will last for at least five years. The team has come together to understand how periods of low or high salinity, changes in the amount of oxygen in the water, acidic conditions, and extreme temperatures stress species living in Mobile Bay. The researchers and resource managers are united in confronting these stressors.

‘How do you manage the whole system, not just one particular resource?’

Lehrter considers the Dauphin Island Sea Lab (DISL) a special place for marine scientists. “I can look out my window, and I can see the Gulf of Mexico. And then I go over to the other side of the building, and we’re right at the bottom of Mobile Bay. Being able to get in the boat and, within five minutes, being out collecting data, it’s just a great place to be.” It’s here where he conducted his graduate research and later returned as a faculty member in 2016.

Before returning to become a professor and associate director of the Stokes School of Marine & Environmental Sciences at the University of South Alabama and senior marine scientist at DISL, Lehrter spent time as a private consultant and federal scientist. He was both intrigued by and frustrated with the disconnect between the reality of many stressors having an impact on the environment and the single-stressor focus of so much science that has been conducted so far.

“There’s climate change, there’s changes in river hydrology, local shoreline development. There’s just a collection of things that are happening to all of these systems simultaneously,” Lehrter said. “I realized that working on these things sort of in a one-off manner, we weren’t really ever going to get the answer about why so many coastal species are in decline, because there are separate drivers, but they all interact with each other, unpredictably.”

When the NOAA RESTORE Science Program’s 2019 funding opportunity on environmental variability and trends was released, Lehrter was ready to pursue this “once in a career opportunity” with interesting science questions, a team of collaborators, and invested stakeholders.

The team asked themselves, “what can we do locally?” and proposed to look at multiple, local stressors within Mobile Bay. However, given the large watershed of Mobile Bay and the influence of climate change, the team also knew they would need to move up in scale to larger watershed stressors to still larger regional and global changes to understand the true context of stress on the Mobile Bay system. They honed in on three species, oysters, blue crabs, and spotted seatrout, due to their cultural and commercial importance as well as the strong management interest from the state of Alabama.

Dr. Amy Hunter, Deepwater Horizon restoration coordinator with the ADCNR, recognized the application potential of this research to her Department’s focus on water quality. She was and remains most excited about the project contributing to the foundational knowledge and holistic view of Mobile Bay, and getting one step closer to answering “how do you manage the whole system, not just one particular resource?”

‘It made sense to me to not just look at one little part of the equation’

To effectively cover multiple stressors over multiple spatial scales and time periods, the project needed the right set of people and diverse methodologies. Computer modeling would be core to the research effort to look to the past and the future. The model the team is developing connects climate data; what enters the bay from the watershed; how water moves in the bay and how the biology, geology, and chemistry of the system interact.

The team decided to utilize historical datasets from Alabama. “We were going to be limited just because of the nature of sampling and some projects start and they die. So we knew that we would need to have modeling involved in this to really get a long-term historical perspective,” Lehrter noted.

Working through archives collected by ADCNR’s Marine Resources Division is Hannah Ehrmann, a PhD student in Dr. Ronald Baker’s lab at the University of South Alabama and one of the seven graduate students contributing to the RESTORE project. Ehrmann’s interest in the whole ecosystem and previous research on benthic infauna set her on the path to this experience. “I always wanted to include the fishery species as well. It made sense to me to not just look at one little part of the equation,” Ehrmann said.

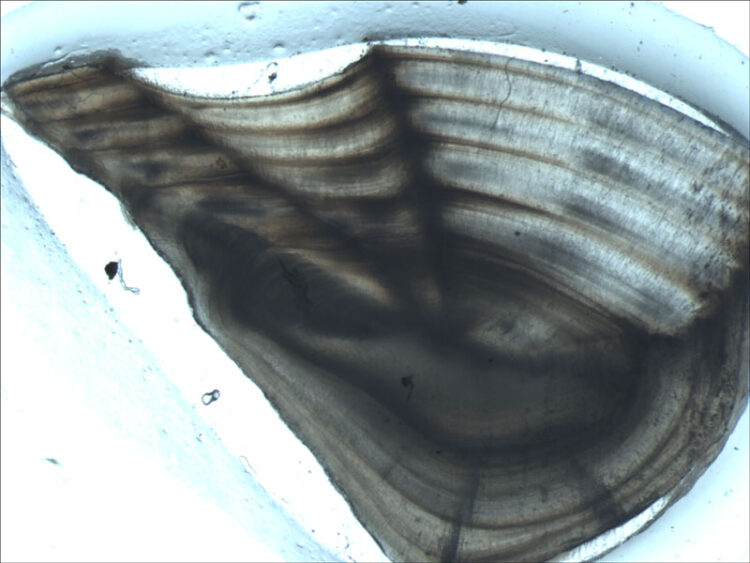

For her dissertation, Ehrmann focuses on juvenile sport fish and what factors in the environment drive their individual growth, a population’s recruitment into the fishery, and the changing composition of rare and abundant species. She needed a long-term dataset to explore these questions and was fortunate to find one with Mareska and his staff. The Marine Resources Division keeps and collects a 20-year otolith, or earstone, catalog that Ehrmann could use to determine fish growth.

“We measure the distance between the rings compared to the distance to the radius of the otolith to get an approximate measure for how much that fish has grown in each year. So then I have these index growth values for each year and for each cohort of fish,” Ehrmann described.

As she finishes imaging the otoliths and measuring the rings of growth, the next step is to add in the environmental stressors and understand their contributions to differences in growth. Her dissertation research contributes to the team’s plan to develop an understanding of the historical trends and variability with the model, and link these trends and variability to changes in the populations of the three species of interest.

To support the model, the project includes field and lab components to validate the modeling results, earn the trust of intended users, and provide foundational knowledge detailing the impact of single and multiple stressors on the three species. Economists are surveying Gulf coast populations on their preference, or willingness to pay, for these three species. The results of this ecosystem service valuation will allow the managers to account for the perspectives of Gulf coast communities dependent on the resources as they consider management options.

“The idea is to include all of this understanding into our modeling framework, and then work with our stakeholders to develop the scenarios that they want to test,” Lehrter said.

‘A picture is worth a thousand words, but an animation is worth thousands’

The model of Mobile Bay bridges the gap between researchers and intended users. “I always say a picture’s worth a thousand words, but an animation is worth a thousand thousands if you can put it in motion. You can show people where that runoff is going and then where it goes in the bay and how it affects water quality and habitats,” Lehrter said.

The holistic and large scale model is important to state natural resource managers like Hunter. Seeing the researchers run the model firsthand, Hunter appreciates the opportunity to learn something new about the system she is tasked to care for. “When I sit and watch him run the salinity model, or watch his team run it, there are plenty of times that I thought, huh, I wouldn’t have guessed that it worked like that in that particular portion of the bay.”

The model also provides the state managers the chance to make proactive decisions. Mareska and his staff are especially interested in understanding the hydrodynamics of the bay and how changing conditions will affect oysters. The researchers and managers are starting to realize the model’s connection to management actions.

“Typically, our toolbox is, we have size limits, we have bag limits and seasonal closures. If these models can help us predict when we would have good or poor recruitment years, then subsequently, in the next year, we could make some management decisions to modify seasons, bag limits and so forth,” Mareska said.

Lehrter and his team can now demonstrate the impact stressors, like marine heat waves, can have on oyster recruitment and increase the managers’ confidence in making proactive decisions. “That’s where this is all coming together in terms of informing ecosystem-based management that includes not only the fishery side, but the bottom-up processes, the physics and the biogeochemistry, that also influence the success of year classes and recruitment into the fishery,” Lehrter said.

Gatherings with the researchers and intended users are a space to learn from each other and strengthen the Mobile Bay community’s commitment to work together. “The information and knowledge exchange at these meetings builds capacity. State resource managers stay up to date on the state of the academic research in our own backyard – Mobile Bay. Scientists on Lehrter’s team learn about all the restoration, management, and monitoring efforts ADCNR is conducting. These dialogues focus the science, inform restoration, and strengthen our collaboration,” Hunter highlighted.

These meetings also demonstrate to the next generation of scientists, like Ehrmann, what working together for ecosystem-based management looks like. “We do our science presentations, but we also get to sit there and ask, ‘can we take this project in a different direction? Is this helpful research?’ We just get to have those conversations, and it’s very cool being a part of such applied research.”

Cover photo by Karkinos19, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Official websites use.gov

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Official websites use.gov

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.